It is very common in Australian schools to “stream” students for subjects such as English, science and maths. This means students are grouped into different classes based on their previous academic attainment, or in some cases, just a perception of their level of ability.

Students can also be streamed as early as primary school. Yet there are no national or state policies on this. This means school principals are free to decide what will happen in their schools.

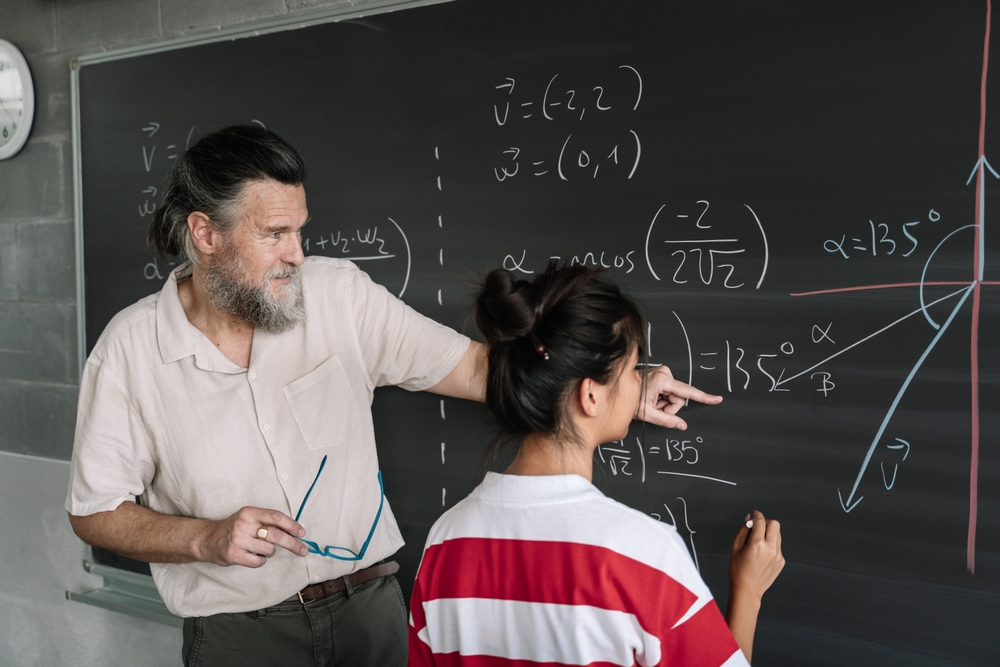

Why are students streamed in Australians schools? And is this a good idea? Our research on streaming maths classes shows we need to think much more carefully about this very common practice.

Why do schools stream?

At a maths teacher conference in Sydney in late 2023, I did a live survey about school approaches to streaming.

This survey was done via interactive software while I was giving a presentation. There were 338 responses from head teachers in maths in either high schools or schools that go all the way from Kindergarten to Year 12. Most of the teachers were from public schools.

In a sign of how widespread streaming is, 95 per cent of head teachers said they streamed maths classes in their schools.

Respondents said one of the main reasons is to help high-achieving students and make sure they are appropriately challenged. As one teacher said:

[We stream] to push the better students forward.

But almost half the respondents said they believed all students were benefiting from this system.

We also heard how streaming is seen as a way to cope with the teacher shortage and specific lack of qualified maths teachers. These qualifications include skills in both maths and maths teaching.

More than half (65 per cent) of respondents said streaming can “aid differentiation [and] support targeted student learning interventions”. In other words, streaming is a way to cope with different levels of ability in the classrooms and make the job of teaching a class more straightforward. One respondent said:

[we stream because] it’s easier to differentiate with a class of students that have similar perceived ability.

The ‘glass ceiling effect’

But while many schools and teachers assume streaming is good for students, this is not what the research says.

Our 2020 study, on streaming was based on interviews with 85 students and 22 teachers from 11 government schools.

This found streaming creates a “glass ceiling effect” – in other words, students cannot progress out of the stream they are initially assigned to without significant remedial work to catch them up.

As one teacher told us, students in lower-ability classes were then placed at a “massive disadvantage”. This is because they can miss out on segments of the curriculum because the class may progress more slowly or is deliberately not taught certain sections deemed too complex.

Often students in our study were unaware of this missed content until Year 10 and thinking about their options for the final years of school and beyond. They may not be able to do higher-level maths in Year 11 and 12 because they are too far behind. As one teacher explained:

they didn’t have enough of that advanced background for them to be able to study it. It was too difficult for them to begin with.

This comes as fewer students are completing advanced (calculus-based) maths.

If students do not study senior maths, they do not have the background for studying for engineering and other STEM careers, which we know are in very high demand.

On top of this, students may also be stigmatised as “low ability” in maths. While classes are not labelled as such, students are well aware of who is in the top classes and who is not. This can have an impact on students’ confidence about maths.

What does other research say?

International research has also found streaming students is inequitable.

As a 2018 UK study showed, students from disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to be put in lower streamed classes.

A 2009 review of research studies found that not streaming students was better for low-ability student achievement and had no effect on average and high-ability student achievement.

What should we do instead?

Amid concerns about Australian students’ maths performance in national and international tests, schools need to stop assuming streaming is the best approach for students.

The research indicates it would be better if students were taught in mixed-ability classes – as long as teachers are supported and class sizes are small enough.

This means all students have the opportunity to be taught all of the curriculum, giving them the option of doing senior maths if they want to in Year 11 and Year 12.

It also means students are not stigmatised as “poor at maths” from a young age.

But to do so, teachers and schools must be given more teaching resources and support. And some of this support needs to begin in primary school, rather than waiting until high school to try and catch students up.

Students also need adequate career advice, so they are aware of how maths could help future careers and what they need to do to get there.

Author

Elena Prieto-Rodriguez

Professor, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article here.